High Alert Institute

Did We Ever REALLY Ask?

Hospitals and their corporate officers live and die by customer satisfaction scores such as the Press/Ganey Survey and Harris Poll. The problem is that these “surveys” & “polls” are little more than “opt-in” commentaries. Scientific data shows that, regardless of industry, a dissatisfied customer is three times more likely to express their opinion than a satisfied customer. Given this fact, the healthcare industry standard “opt-in” model, by its very nature, should yield a 3 to 1 dissatisfaction bias. Given that this bias is not seen indicates that other, unaccounted for factors, are skewing the data.

Survey Construction

To obtain meaningful data from a survey or poll, specific criteria for data collection must be met. The first and most important is that the demographic make-up of the study group must be determined before the data is collected. Demographics includes more than gender, age and ethnicity. In the healthcare setting, treatment area specific identifiers such as time of year, triage level on presentation (ESI 1-5), initial evaluation and management level (E/M 1-5), waiting room wait time, length of stay, etc. allow for further differentiation of individual factors influencing patient sentiment and satisfaction.

These demographic groups must be strictly adhered to and once the number of a particular group is obtained for a given survey, no further survey responses are accepted in that demographic group. Further, if a particular demographic group is not fully enrolled with respondents, additional individuals are recruited in that demographic group only until the required number of responses are obtained. This is currently not done in healthcare, yet it is the key to obtaining interpretable data.

Questions Are Key

In healthcare, the rule is to ask open ended questions to obtain global information and then ask close ended questions to obtain specificity. In survey construction, specific questions must be asked before the survey is constructed. Like a scientific investigation (and all valid surveys are scientific investigations) the first question is to ask what specific and narrow question we seek to answer. Commonly, the response from corporate leaders is that they want to know if customers are satisfied, but this is not sufficiently specific. Which customers? Under what circumstances? Such a customer satisfaction question would be,

“Are customers with an ER lobby wait of greater than 4 hours (all other demographic factors being equal) more satisfied customers than those with a lobby wait greater than 4 hours?”

Once the question is narrowed to a specific single area, a null question (null hypothesis) must be formed. This is a testable question such as,

“Is there a difference between customers with an ER lobby wait of greater than 4 hours (all other demographic factors being equal) and those with a lobby wait greater than 4 hours?”

This latter question can be answered easily by having a demographically specific and identical group score their satisfaction then dividing them based on their lobby wait time. A simple comparison of the satisfaction scores between the two groups will then indicate the influence of lobby wait on satisfaction. Obviously, those with different demographic factors will respond to wait times differently and thus narrow demographic groups with large numbers must be studied to determine if lobby wait is in fact a factor at all.

Acknowledge Framing Bias

The construction of a survey or poll must also include a consideration of the bias held by those asking the questions. Failure to acknowledge even seemingly unrelated bias will inevitably skew the results due to the framing of the question. Referring back to the ER lobby wait example above, most in healthcare leadership hold the belief, based only on unscientific “opt-in” commentaries, that ER lobby wait is a key factor in customer satisfaction for all ER patients (regardless of other demographics). This bias results in customer satisfaction studies that are skewed to elicit comments congruent with that bias such as,

“Was your ER wait time short, adequate, long, excessive?”

This question primes the reader to view a long ER wait (even for a non-emergency) as excessive if it is longer than they wanted. The unbiased approach would be to determine ER wait time as a demographic factor based on the time from sign-in (arrival) to the time place in a room (door to room time). Having this information, the question would then be,

“Please rate your overall satisfaction on a scale of 1 through 5 (1 = very dissatisfied & 5 = very satisfied)”

The statistical comparison of overall satisfaction between those with an ER lobby wait under 4 hours and those with a wait over 4 hours within otherwise matched demographic groups yields an accurate reflection of the impact of ER lobby wait on overall satisfaction.

Bad Questions Yield – Bad Conclusions

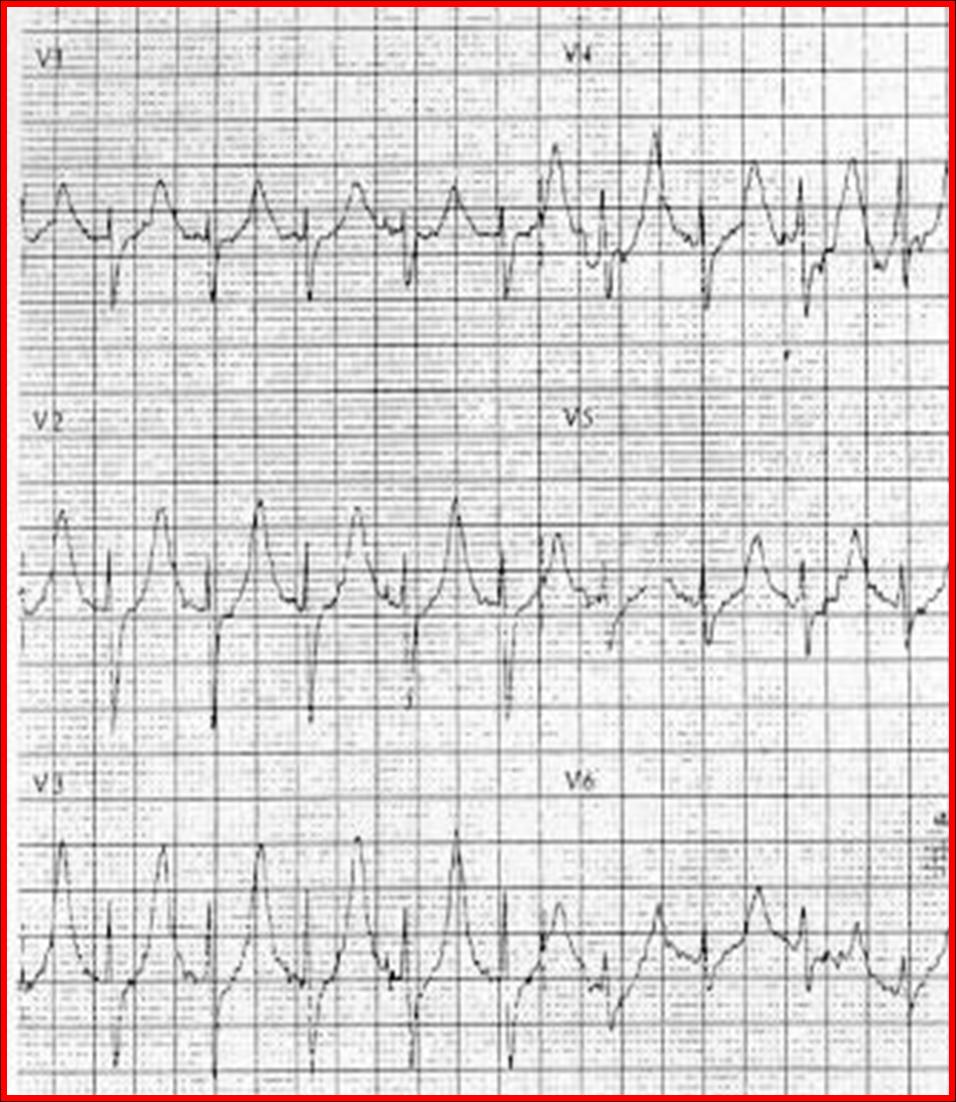

Just in case there is any doubt of the influence of bias, an “opt-in” commentary invitation was placed on the internet for seven days and circulated using a professional networking service. An analysis for power determined that 53 respondents were required for statistical significance.1 Like all healthcare customer satisfaction surveys currently employed, any person having been an ER patient was included in the final analysis.1 Over 28,900 individuals viewed the question, but only 59 “opted-in” with responses.1 A heuristic analysis for bias was preformed to generate a question that minimized bias based influence on responses.1 The resultant question asked,

“Given that your wait in the lobby and your total time in the ER would be unchanged, would you rather have your ER doctor come into the room 10 minutes after you are brought from the lobby to introduce themselves but do nothing else, or would you rather have your ER doctor come into the room 25 minutes after you are brought from the lobby and complete the entire interview, exam and ordering of tests/treatment?” 1

The 10 minute option and the 25 minute option represent the current ER incarnations of LEAN and Six Sigma respectively. Pre-study review of the ER management literature found that the majority of the responses would prefer one of the other, but there was no consensus on which option would be preferred.1

Surprisingly, out of 59 responses, 1% offered no preference, 53% preferred the 25 minute wait and 46% preferred the 10 minute wait.1 Of greater interest, one in twenty of those who preferred the 10 minute wait stated that they only preferred it because they could “bully” the doctor into staying and completing the entire patient encounter rather than leaving after the introduction.1 Despite respondent reframing of the options, there was still no statistically different difference between the options.1

While each of these approaches have ardent supporters who insist that their approach is the solution to low patient satisfaction, this data suggests that the right question has not yet been asked and thus the true answer has not yet been found.

Asking a Better Question – Getting Better Answers

Asking better questions often yields surprising and useful information. Markoul, Zick and Green published a survey based study looking at how patients prefer to be addressed when they first meet their healthcare provider. In most healthcare encounters, physicians greet patients by either first name or title with last name while introducing themselves with their title and last name. Conversely, nurses are taught to great patients by first name and introduce themselves by first name only. Across the board, all healthcare providers are counseled to offer a handshake at every encounter.

Answering closed-ended, narrowly constructed questions, a survey of 415 patients found that 50% the patients wanted their first name to be used when physicians greet them.2 Similarly, 16% of patients preferred to be greeted by their title and last name, and 24% wanted their first and last names to be used.2 As to how healthcare providers should introduce themselves to the patient, 56% wanted to hear both names; 33% wanted the provider to use just their title and last name, and only 7% wanted first names to be used.2 Approximately 78% of respondents expected to receive a handshake, with older patients less likely than younger patients to want a handshake (74% vs. 87%; P < .005).2

This data shows that the broadest group of patients would be satisfied if their provider greeted them using first and last name names (satisfying all three groups). Further, providers should introduce themselves using title with both first and last name while offering a handshake (again satisfying all groups).

Getting to the Answers Needed

Patient and customer satisfaction surveys are a fact of life in the business of healthcare. Improving these critical business benchmarks is too often linked to hastily contrived and implemented process changes. If the key to making the best decisions is having the best information and the key to having the best information is asking the best questions to the right groups of people, then before the next survey is sent out, healthcare must create better surveys.

- Determine the distinct demographic groups to be surveyed

- Determine the exact number from each group to be surveyed

- Survey exactly that number from each group (no more and no less)

- Determine the question to be answered and the null question to ask

- Acknowledge framing bias and frame the null question without that bias

- Limit conclusions to the answer for the null question

- Use inconclusive results as a guide to identifying factors without influence on customer satisfaction

- Use conclusive results as a guide to identifying actions that will improve customer satisfaction

When healthcare really asks patients for the answers it seeks, customer satisfaction scores will become irrelevant because patients will automatically get what they need and deserve.

High Alert Institute

4800 Ben Hill Trail

Lake Wales, FL 33898

Office: 863.696.8090

FAX: 407.434.0804

EIN: 27-5078437

Info@HighAlertInstitute.org

Privacy Policy

Cookie Policy

Terms of Use

Disclaimers

Get Your Data

Shipping Policy

Message Us

Transparency

Registrations

Do Not Sell Info

Return Policy

A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING TOLL-FREE, WITHIN THE STATE, 1-800-435-7352 (800-HELP-FLA), OR VISITING www.FloridaConsumerHelp.com. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE. Florida Registration #CH68959

REGISTRATION WITH A STATE AGENCY DOES NOT CONSTITUTE OR IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL OR RECOMMENDATION BY THAT STATE.